Please vote today. Let your voice be heard. And if you find yourself thinking “my vote doesn’t matter,” please read this article by Jocelyn Y. Stewart—and then go cast your ballot. Click here to read “People Died So I Could Vote.”

Author Archives: Curtis Spears

Our Brothers…or Aliens?

During my first days as a commander in the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, Assistant Chief Mike Graham gave me a special assignment. He asked me to organize and head a committee, assess our gang enforcement efforts and make recommendations.

During my first days as a commander in the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, Assistant Chief Mike Graham gave me a special assignment. He asked me to organize and head a committee, assess our gang enforcement efforts and make recommendations.

That’s when I began to take a close look at a youth program called VIDA.

Kids between the ages of 11 and 17 entered VIDA engaged in the kind of behavior and thinking that would one day land them in prison. But after 16-weeks of intense intervention, they were different kids: better attitudes, better outlook, equipped to make better choices. VIDA was created by patrolmen Drew Britness and Vince Romero, who’d relied on their experiences in the streets to design a winning program.

After witnessing the success of VIDA, I recommended we expand it from East L.A., where it first operated, to other areas of Los Angeles County. The expansion would mean more kids would have an opportunity to change and become better.

The expansion suggestion was well received and VIDA now operates in eight locations—and helps a lot more kids. It’s staggering to think of what the county would look like without VIDA.

This is why I applaud President Obama’s “My Brother’s Keeper” initiative, which is designed to create opportunities for boys and young men of color. Too often we hear people talk of our youth as if they are aliens, here from another planet. They are different, hard to understand, beyond our ability to help.

The truth is that you can visit any city in the nation and find youth programs that work. These programs are saving youth from dropping out of school, joining a gang, using and selling drugs, and engaging in violence and other criminal activities. The programs are setting kids on a right path.

What you might find missing in Any City, U.S.A., is the political will, interest, and resources needed to expand the most effective programs. Faced with this lack, youth statistics worsen. And we hear more about the aliens: The real problem is those kids are just so different.

But these are our children. Like every other generation they deserve the opportunity to have the tools they need to reach their fullest potential. They deserve a healthy environment in which to learn and grow. They deserve our best. We must approach our youth, not with a sense of futility, but with a dogged determination to find solutions.

“My Brother’s Keeper” includes a task force that will determine which public and private efforts are working and how the government can encourage those efforts. This initiative is a real opportunity to save our brothers, sons, nephews, uncles, the neighbors’ boy. I look forward to seeing the outcome.

And while we’re at it, please let’s not forget our girls. Ask any elementary, middle school, high school teacher and he or she will tell you about the trouble with girls…But that’s a topic for another blog post.

(To read more about VIDA, which stands for Vital Intervention and Directional Alternatives, click here: http://www.vida.la/aboutUs.php You can read more about my days as a commander in my book “Way, Way Up There: My Odyssey from Cotton Picker to Top Cop”)

Living the News

Once when I was a sergeant with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, I went to the bank to deposit a check and found myself in the middle of a bank robbery. I was off duty, in plain clothes, and had left my gun in the car.

I hadn’t gone to the bank as a cop intent on arresting bad guys. I was just an unassuming customer—with bad timing. Now I knew what a robbery victim felt. I talk more about this in my book “Way, Way, Up There: My Odyssey from Cotton Picker to Top Cop.”

Veteran journalist Jocelyn Y. Stewart experienced a similar kind of turnaround. Instead of reporting about another senseless act of violence, she found herself speaking at a press conference asking for the public’s help to find the killer of a loved one.

Jocelyn wrote about this experience recently in the online magazine, Narrative.ly. Here’s the beginning of her story, “Grief Has No Deadline.”

* * *

To be a reporter in a city like Los Angeles is to understand the redundancy of crime.

Bullets strike—and then strike again. A young life ends—and then another. Grieving parents wonder how to survive the aftermath, when birthdays and Christmas mornings arrive and their child is gone.

The reporter who covers the crime won’t be present for the aftermath. The reporter will move on to the next story. Such is the reality of big city reporting. For years, that reporter was me. At the Los Angeles Times for nearly two decades and then as a freelance writer, I experienced the “on-to-the-next-story” life.

Then one sunny afternoon, I found myself at the 77th Division of the Los Angeles Police Department for a press conference about a twenty-two-year-old man who’d been fatally shot while driving in South Los Angeles early in the morning of April 21, 2012.

This time the tearful relatives standing before the cameras and the reporters were mine. The victim wasn’t somebody else’s child. He belonged to us. Kendrick LaJuan Blackmon, a.k.a. Lil Bit. My nephew.

At scenes like this, for so long my place had always been among the reporters, asking the questions, gathering facts and taking down quotes before rushing off to make deadline. Now I stood on the other side of the podium watching the journalists scribble notes as we pleaded for the killer to come forward.

This time there would be no moving on to the next story. I wouldn’t write about this for the next day’s paper. I would live it for years to come, because grief has no deadline.

* * *

There is a time of night when a phone call almost always means some kind of trouble, some news that will make your heart sink.

On April 21, 2012, at about two a.m., my house phone rings and awakens me from sleep. The voice on the other end is my niece, Shanae.

“Jo?” she says.

“What’s wrong?”

“They shot Lil Bit!”

In one motion, I am out of bed, dressed, and in my car on the freeway, headed to South Los Angeles. At that hour the freeway transition road is empty except for my car. This part of the freeway is elevated, so high you can see miles and miles of city lights, neon signs and billboards. All of it sits beneath you, seemingly peaceful, even surmountable. This is a good place to talk to God.

Not Lil Bit. Please Lord. Let him live.

To read the full story click here: http://narrative.ly/unsolved-mysteries/grief-has-no-deadline/

A Year Well Spent

On Sunday 60 Minutes ran a segment featuring Year Up, an innovative year-long training program that offers young people hands-on skills development, college credit, and a corporate internship.

On Sunday 60 Minutes ran a segment featuring Year Up, an innovative year-long training program that offers young people hands-on skills development, college credit, and a corporate internship.

Viewers of 60 Minutes discovered what Year Up fans and Twitter followers know: Year Up is changing the lives of young adults in positive and lasting ways.

If you missed the 60 Minutes segment, check it out here on Year Up’s website: www.yearup.org

Thanks to Year Up for the excellent work. Thanks to 60 Minutes for the great coverage. And most of all, congratulations to the young adults featured in the segment. May you realize all your dreams and inspire others to do the same.

Here’s hoping the 60 Minutes coverage will help Year Up continue to empower young adults.

A Tale of Two Patients—and One Deadly Form of Discrimination

Consider the experience of these two patients:

Consider the experience of these two patients:

Patient One has a heart attack. He goes to a hospital, and like most patients who have suffered a heart attack or have pneumonia, he is admitted. An electronic notice will be sent to his insurance company the next business day.

Patient Two is deeply depressed and has tried to commit suicide. He goes to a hospital for help. Before treating the patient, the doctor first must call a toll-free number, “present the case in voluminous detail, and get prior authorization,” Dr. Paul Summergrad, president-elect of the American Psychiatric Assn., said in a recent New York Times article.

Why the difference?

For decades insurance companies have been allowed to treat mental illness as if it is somehow not a real disease. Their rules and regulations made it tougher for a person suffering from mental illness or addiction to get help. While this may help an insurer’s bottom line, it does nothing to help our society.

Mental illness has been a major factor in many of the mass shootings that have devastated our nation, from the Newton, Conn. elementary school massacre, to the killings at a Naval shipyard in Washington, D.C. Drug addiction plays a major role in many more crimes every day in this country. Just ask any cop.

Treating mental illness and addiction the same way we treat physical illness seems like common sense, but insurance companies have done just the opposite—until now.

Last week, the New York Times reported that the Obama Administration completed an effort to require insurance companies to cover care for mental health and addiction the same way they cover physical illnesses.

The long-awaited regulations defining parity in benefits and treatment have been many years in the making. And they are a critical part of the president’s plan to reduce gun violence. According to the New York Times, the regulations address “an issue on which there is bipartisan agreement: Making treatment more available to those with mental illness could reduce killings, including mass murders.”

The regulations will also extend to people covered by the Affordable Care Act. These new rules are expected to be particularly helpful to returning veterans, such as those suffering from post traumatic stress disorder.

As we continue to search for a way to end the violence that terrorizes this nation, this is a major step in the right direction.

Jail or Yale: The Cost is Nearly the Same

It costs nearly as much to house an inmate in a New York City jail as it does to educate a kid at an Ivy League School, according to a Washington Post article published yesterday.

New York spends $167,731 per inmate annually—about the amount parents will pay in tuition fees for four years of education in the Ivy League. That breaks down to $460 a day. However you slice it, the number is astounding.

Experts point the finger of blame at Rikers Island. This 400-acre island is home to 10 correctional facilities and thousands of employees. It’s expensive to run for a variety of reasons. To read the entire Washington Post article, click here.

One alternative is to replace Rikers Island with neighborhood jails located next to courthouses. But that politically unpopular plan was foiled by opposition from residents who live near courthouses. In the meantime, the price tag for incarceration in New York jails continues to skyrocket. And the loud opposition one might expect is not there.

Martin F. Horn, a former city correction commissioner, told the Washington Post: “My point is: Have you seen a whole lot of outcry on this? Why doesn’t anything happen?” Horn said of the $167,731 annual figure. “Because nobody cares.”

“That’s the reason we have Rikers Island,” he said. “We want these guys put away out of public view.”

Keep in mind that we’re not talking about prison. This is city jail. The population includes people who are awaiting trial. That means New York City is spending Ivy League money not only on hardened, violent criminals, but on drug addicts and small time criminals. At least some of the inmates will be found not guilty and will be released, or the charges will be dropped.

We all should be concerned with public safety. But numbers like this beg obvious questions. Isn’t there a better way? Why is the public OK with this kind of outlay of funds? Isn’t there a better way to spend this money?

Think about it: If New York City spent an average $167,731 a year to educate a high school student, or to re-train a laid-off laborer, or to feed, clothe and house a poor family, or to eliminate the digital divide, what would the public say?

Think of what organizations like Black Girls CODE, Girls Who Code, Hidden Genius Project, Year Up and others dedicated to STEM education could do with such abundance. How many disadvantaged youth would grow up to become computer programmers or engineers because of their experiences in groups like these? (Click on the name of the organization to go to their website and learn more about the great work that they do.)

But you can imagine the outcry—which is why the silence now is so loud.

Guns in the Hands of Children and the Mentally Ill–A Recipe for Violence

A recent string of violent incidents has forced the nation to again question the roots of violence.

• In Slaughter, Louisiana, an 8-year-old boy played the violent video game Grand Theft Auto, then shot his 90-year-old grandmother in the back of the head, killing her.

• In the Washington, D.C., area a former Navy reservist, who was known to play violent video games for hours, and had displayed signs of mental instability, walked into a navy yard and shot and killed 12 people. The New York Times reported that Aaron Alexis was armed with an AR-15 assault rifle, a shotgun and a semiautomatic pistol.

• In Chicago, four young men were charged in the shooting of 13 people who had gathered to watch a basketball game. The injured included a three-year-old.

Last week on its first day of release, Grand Theft Auto V, generated a whopping $800 million in retail sales worldwide. The success of the GTA franchise is unparalleled—and its makers are unfazed by the critics who see a link between violent video games and gun violence. Millions of people have played some version of Grand Theft Auto and have not committed homicide.

Yet, the killings continue. The link between video games and violence may be debatable, but in my mind one point is painfully clear: children and crazy people should not have access to guns.

This is a simple concept that many people can agree on and accept. But when it comes to enacting the laws and policies that would transform that concept into reality, the gun lobby pulls out…the big guns. Any attempt to modify gun laws meets with derision, scare tactics, a campaign to paint gun control as an attack on the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, the American way, and your personal safety.

And the killings continue.

The idea that more guns in America equals a safer America simply does not wash. One horrific event after another proves that more guns have resulted in more accessibility. When even eight-year-olds and the mentally ill can access guns something is terribly wrong.

This may come as a surprise to some of my brothers of the badge, but I believe it’s time to have serious discussions about responsible gun ownership and about limiting access. It’s time to talk without the rabid rhetoric and scare tactics. As a nation we are innovative enough and brave enough to create a way to keep guns away from those who should not have them, while maintaining access for others. After all, working together to resolve our problems is really the American way.

Troubled Youth…and an Old Typewriter

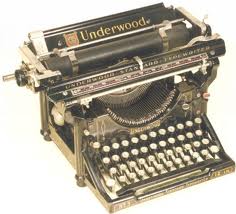

A century ago the Underwood typewriter was high technology. It was the latest, the best, the “must have” device for anyone in the business of communicating. Talk to the average kid today and most have never even seen an actual typewriter—and they certainly haven’t used one. The typewriter for them is a relic of a long ago past.

A century ago the Underwood typewriter was high technology. It was the latest, the best, the “must have” device for anyone in the business of communicating. Talk to the average kid today and most have never even seen an actual typewriter—and they certainly haven’t used one. The typewriter for them is a relic of a long ago past.

Our methods of communications have advanced at break neck speeds; our social policies concerning troubled youth have not. By comparison, over the years we have crawled toward more effective and humane policies; and our slow pace has cost us lives that could’ve been saved. According to the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the U.S. still leads “the industrialized world in the rate at which we lock up young people.”

“In every year for which data are available, the overwhelming majority of confined youth are held for nonviolent offenses. In 2010, only one of every four confined youth was locked up based on a Violent Crime Index offense (homicide, aggravated assault, robbery or sexual assault).”

“40% OF JUVENILE COMMITMENTS AND DETENTION ARE DUE TO technical violations of probation, drug possession, low-level property offenses, public order offenses and status offenses (activities that would not be considered crimes as adults, such as possession of alcohol and truancy). This means most youth are confined on the basis of offenses that are not clear threats to public safety.”

Since 1995 the overall picture has started to improve. From a peak in 1995, the rate of youth in confinement dropped by 41% in 2010. But we still have a long way to go. Huge disparities exist between the confinement rates of youth of color in comparison to their white peers. The Annie E. Casey Foundation reports:

“African-American youth are nearly five times as likely to be confined as their white peers. Latino and American Indian youth are between two and three times as likely to be confined. The disparities in youth confinement rates reflect a system that treats youth of color, particularly African Americans and Latinos, more punitively than similar white youth.”

Imagine what would happen if we as a nation addressed the problems of youth with the same creativity, innovation, resources, interest and drive that took us from the Underwood typewriter to the iPhone. How would our policies look? What would our youth confinement rate be then?

America’s Juvenile Justice System: Part of the Problem or Part of the Solution?

David Tyrone is 15-years-old. He’s an average student, who attends school regularly, and secretly dreams of becoming an artist. David knows gang members—it’s hard to live in his neighborhood and not know them—but he doesn’t belong. He’s not sure the gang life is for him. One day after school, David accepts an invitation to ride with his friends to the mall. That evening he and his friends are arrested for joy-riding. David is sentenced to time in a juvenile detention center. Inside he’s a target. When people ask him where he’s from, his answer, “nowhere,” is never good enough. In juvenile detention, you have to be from some gang. Inside you need protection—or else. David gravitates toward the gang members from his neighborhood. They protect him. They school him. By the time he’s released from juvenile detention, David is changed. Now he’s a bona fide gang member. Now he’s got “creds” (a reputation). It’s almost certain that he’ll return to juvenile detention for some crime or another.

David Tyrone is 15-years-old. He’s an average student, who attends school regularly, and secretly dreams of becoming an artist. David knows gang members—it’s hard to live in his neighborhood and not know them—but he doesn’t belong. He’s not sure the gang life is for him. One day after school, David accepts an invitation to ride with his friends to the mall. That evening he and his friends are arrested for joy-riding. David is sentenced to time in a juvenile detention center. Inside he’s a target. When people ask him where he’s from, his answer, “nowhere,” is never good enough. In juvenile detention, you have to be from some gang. Inside you need protection—or else. David gravitates toward the gang members from his neighborhood. They protect him. They school him. By the time he’s released from juvenile detention, David is changed. Now he’s a bona fide gang member. Now he’s got “creds” (a reputation). It’s almost certain that he’ll return to juvenile detention for some crime or another.

David Tyrone is not a real kid, but this dilemma is very real. Scenarios like this play out every day in cities across America. It’s time to ask ourselves the question: do our juvenile justice detention centers deter the proliferation of juvenile gangs and the attendant gang violence or do they inadvertently serve as recruitment centers for gangs?

As our detention centers become more crowded and violent, many offenders who were incarcerated for non-gang related offenses are drawn into gangs for protection They quickly realize that inmates/youth who are not affiliated with any gang set are easy prey for gang members from any of the different warring sets. The basic tenet of our juvenile justice system is rehabilitation. With the overcrowding, staff shortages and the increasing tensions between warring gang factions, more time is being spent on safety issues and less on rehabilitative efforts. Part of the problem is this: some kids simply do not belong in juvenile detention.

To really appreciate this dilemma, an at least cursory examination of the gang infrastructure is needed. Think of the gang hierarchy as an inverted triangle. At the top and larger part of the triangle are the “wanna-bees” (hangers on who are flirting with the idea of becoming a gang member) and new gang members. The second tier and second largest group are the mid-level members. The last group, which is the smallest and most dangerous, is composed of “shot callers.” Very little of consequence occurs in a gang set without the knowledge or direction of the shot callers. Unfortunately, our juvenile justice system sometimes treats these categories of youth the same. Distinguishing between the groups can mean the difference between saving a kid from a life of violence and pushing him down a treacherous path.

We can be doing a lot more than institutionalizing youth, especially the wanna-bees and new gang members. To effectively impact the issue, more attention/efforts must be focused on prevention. “At risk” youth and wanna-bees must be identified and programs instituted to steer them to more productive lifestyles. We owe it to our future to focus on creative ways to save youth, rather than lock them up. I submit that the gang issue cannot be arrested away. More than 30 years of strenuous enforcement has proven that. It must be dried up by dealing with at-risk youth before they become caught up in the gang culture.

This week attorney general Eric Holder announced fundamental changes in federal mandatory minimum sentences for drug-related crimes. Holder made this comment during his speech:

“Today, a vicious cycle of poverty, criminality, and incarceration traps too many Americans and weakens too many communities. And many aspects of our criminal justice system may actually exacerbate these problems, rather than alleviate them.”

Our juvenile justice system is exacerbating the problem. The big question is, do we have the resolve to devote the energy and resources to correct the problem? Or do we stand idly by and allow these misguided youth to develop into menaces to society?

A Better Place…A Better Country

Apparently the self-serving statements of a white man out-weighed logic and black eyewitnesses. Variations of this scenario have played out in black communities throughout the country. It is through this prism, shaped by life experiences, that many in the black community viewed the Zimmerman verdict. The nuances of self-defense and ill-advised laws like stand your ground are over powered by one powerful fact. An unarmed black youth en route home from a store was followed and subsequently encountered by an armed white adult and ended up dead. Older black adults, although usually more subdued, likely feel a deeper sense of futility and frustration. This is because their experiences were lived, not anecdotal. That feeling of though a black man occupies the highest office in the land, something they never dared to hope to witness, you are still valued differently than white America.

If my dad was still alive I wonder what he would make of all this. Would he see some striking similarities to Calvin’s death? Would he feel the deep hurt being evidenced in black communities throughout the country? Calvin’s death propelled our move to California to a better life and more opportunities. Maybe, just maybe, Trayvon’s death can propel all of us to a better place, a better country…maybe.